Sylvia Plath’s life is a story of extraordinary literary talent, personal turmoil, and a legacy that continues to provoke intense emotion and debate. Known for her raw, confessional poetry and the groundbreaking novel The Bell Jar, Plath’s work captures the complexities of mental illness, gender roles, and existential despair. Her tumultuous marriage to poet Ted Hughes, her struggles with depression, and her tragic suicide at age 30 cemented her as a cultural icon, but her story is often oversimplified. Beyond the classroom narrative of Plath as a tortured artist lies a deeper tale of ambition, betrayal, and a fiercely contested legacy. Here’s a detailed summary, drawing on historical records and cultural perspectives up to my knowledge cutoff.

Early Life: A Prodigy Under Pressure

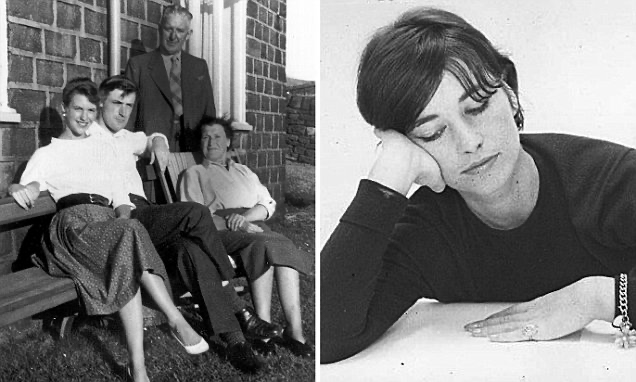

Sylvia Plath was born on October 27, 1932, in Boston, Massachusetts, to Aurelia Schober Plath, a teacher, and Otto Plath, a German-born entomologist and professor. A precocious child, Plath showed early literary promise, publishing her first poem at age eight in the Boston Herald. Her father’s death from diabetes complications in 1940, when Sylvia was eight, was a pivotal trauma, shaping her lifelong struggles with loss and abandonment. Otto’s authoritarian demeanor and Aurelia’s high expectations instilled in Sylvia a drive for perfection, evident in her academic excellence and prolific writing.Plath excelled at Smith College, earning scholarships and accolades, but her ambition was shadowed by mental health struggles. In 1953, after a guest editorship at Mademoiselle magazine in New York, she suffered a breakdown, exacerbated by rejection from a Harvard writing course. Plath attempted suicide by overdosing on sleeping pills, an experience later fictionalized in The Bell Jar. She was institutionalized at McLean Hospital, where electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and psychotherapy helped her recover. She graduated from Smith summa cum laude in 1955 and won a Fulbright scholarship to study at Cambridge University in England.

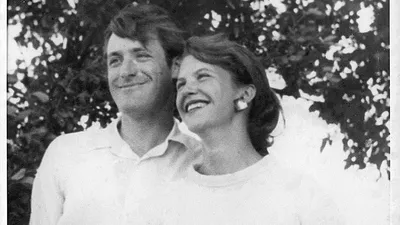

Literary Rise and Marriage to Ted Hughes

At Cambridge, Plath met Ted Hughes, a charismatic English poet, in February 1956. Their chemistry was electric, and they married within four months, on June 16, 1956. Both were fiercely ambitious writers, and their early years were a creative partnership. Plath typed Hughes’s manuscripts, championed his work, and published her own poetry in prestigious journals. Her first collection, The Colossus and Other Poems (1960), showcased her technical skill and vivid imagery, though it received modest attention.The couple moved between England and the U.S., teaching and writing. Plath gave birth to their daughter, Frieda, in 1960, and son, Nicholas, in 1962. Domestic life, however, strained Plath’s mental health and creative output. She idolized Hughes but felt overshadowed by his rising fame, particularly after his collection Lupercal(1960) earned critical acclaim. Plath’s journals reveal her frustration with balancing motherhood, writing, and supporting Hughes’s career, compounded by her recurring depression.

The Bell Jar and Marital Breakdown

In 1961, Plath began writing The Bell Jar, a semi-autobiographical novel about Esther Greenwood, a young woman grappling with mental illness and societal expectations. Published in 1963 under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas (to shield her family), the book was a critical success in the UK but initially overlooked in the U.S. Its unflinching depiction of depression and critique of patriarchal norms later made it a feminist touchstone.By 1962, Plath and Hughes’s marriage was unraveling. They had moved to a rural home in Devon, England, but Hughes began an affair with Assia Wevill, a married woman they met in London. Plath discovered the affair in July 1962, and the betrayal devastated her. The couple separated, and Plath moved to a London flat with their children. In the midst of this emotional chaos, Plath entered a period of extraordinary productivity, writing her most famous poems—later published in Ariel (1965)—in a burst of creative fury. Works like “Daddy,” “Lady Lazarus,” and “Ariel” are searing, confessional, and formally daring, blending personal pain with universal themes of death, rebirth, and rage.

Suicide and Immediate Aftermath

Plath’s final months were marked by despair and resilience. Living alone in London during the brutally cold winter of 1962–63, she struggled with financial strain, single motherhood, and worsening depression. Despite her productivity, she felt isolated, and her mental health deteriorated. On February 11, 1963, Plath sealed the kitchen of her flat to protect her sleeping children, placed her head in the oven, and died by suicide via gas inhalation. She was 30.Her death shocked the literary world. Hughes, who inherited her estate, became the steward of her legacy, editing and publishing her work. Ariel, released in 1965, stunned readers with its intensity and established Plath as a major voice. However, Hughes’s role in her life and death became a lightning rod for controversy. He destroyed parts of Plath’s final journals, claiming they were too painful for their children, and altered the order of poems in Ariel, decisions that enraged Plath’s fans and feminist scholars who saw him as controlling her narrative.

The Legacy: Genius, Rage, and Contention

Plath’s legacy is inseparable from her work and the debates surrounding her life. The Bell Jar and Ariel became feminist classics, articulating the suffocating pressures on women in the mid-20th century. Her poetry, with its raw emotion and technical brilliance, influenced generations of writers. By the 1970s, Plath was a cultural icon, her image as a tragic genius amplified by the feminist movement, which embraced her as a martyr to patriarchal betrayal and mental health stigma.Ted Hughes remained a polarizing figure. His affair with Wevill, who later died by suicide in 1969 (along with their daughter, Shura), fueled accusations that he drove Plath to her death. Feminist activists vandalized Plath’s grave, chiseling “Hughes” off her headstone, and protested his readings. In 1998, Hughes published Birthday Letters, a collection of poems addressing his relationship with Plath, which some saw as an attempt at atonement, others as self-justification. He died later that year of cancer, leaving the debate unresolved.Plath’s children, Frieda and Nicholas, navigated their parents’ legacy in different ways. Frieda became a writer and defended her father’s role, while Nicholas, a biologist, avoided the spotlight. Tragically, Nicholas died by suicide in 2009, reigniting discussions about inherited trauma.

The Untaught Layers

The classroom version of Plath’s story often focuses on her poetry and suicide, but the fuller picture reveals a woman wrestling with ambition, societal constraints, and a volatile marriage. Plath was not just a victim but a fierce artist who channeled her pain into groundbreaking work. The rage her legacy sparks—against Hughes, the mental health system, and gendered expectations—reflects her enduring relevance. Her journals, letters, and unpublished works, later released, show a complex figure: witty, ambitious, and deeply human, not just a tragic muse.Her story also exposes the music industry’s parallels, where image often overshadows authenticity, though Plath’s art was undeniably her own. The controversy over her legacy, particularly Hughes’s editorial choices, raises questions about who controls a writer’s narrative after death. Plath’s work continues to resonate, not just for its literary genius but for its unflinching confrontation with the personal and political forces that shaped—and nearly silenced—her voice.